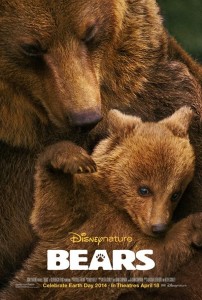

The nature documentary “Bears” hits theaters this Friday, April 18.

The nature documentary “Bears” hits theaters this Friday, April 18.

“Bears” demonstrates the struggles of a bear mother with two cubs in their first year of life as well as social order in the bear community. It also shows predator and prey conflicts constantly, keeping the audience on high alert, wondering what will happen next. The film strays from the typical documentary because it includes humor as well as imaginary dialogue spoken by the narrator. It includes quirky scenes and shots of bears doing silly things that will resonate well with audiences of all ages. The documentary also provides compelling insight to a bear’s hardships not only for survival, but in interactions with other bears. Much of a mother bear’s life is spent obtaining enough food for herself and her cubs, while also protecting her cubs from becoming prey to more dominant bears. From the moment the mother bear wakes from her hibernation slumber, she spends the whole of spring and summer hunting and gathering to build up an adequate fat reserve for the next hibernation period, so she and her cubs can survive. The film then comes full circle with the family burrowing back in their den just in time for winter.

The films directors Alastair Fothergill and Keith Scholey and the legendary Jane Goodall spoke about their work and the film. Jane is a DisneyNature ambassador and spent time in Alaska during the shoot.

What is it exactly that you do?

Jane Goodall: When I got a letter from Lewis Leakey, I’d never been to college, I’ve been with the chimps for a year. He said I had to get a degree to get my own funding, and I had to go straight to a PhD and I would be doing a PhD in Ethology. I had no idea what it meant, and I couldn’t look up Wikipedia in those days, there weren’t even computers invented. Televisions was new. So an ethologist, which is what I am, is actually someone that studies animals, that can even include human animals. But now I think I am a conservationist or an environmentalist. Because I am not studying anymore, but other people are.

What would you say to kids who would want to do what you do when they grow up and what should they do to get there?

Jane Goodall: I was 10 when I decided I wanted to go to Africa, and live with animals, and write books about them, and everybody laughed at me because in those days girls couldn’t do things like that, and we didn’t have any money. But I had a mother who said if you really want to do something you’re going to have to work hard, take advantage of opportunity and never give up. That’s very simple, but if you know… exactly what you really want to do, learn about it, go on the internet to look it up, try to meet people who can help you and never give up.

Alastair Fothergill: Jane that is actually a perfect answer to the question, identical actually, with the “never give up.” A lot of people will tell you that you can’t do things, lots of people.

Jane Goodall: See, I left school, we had no money, I couldn’t go to university, so mom said, maybe you can do a secretarial course, because we can just about afford that, then perhaps you can get a job in Africa. That’s actually what happened. But to get to Africa, I had to work as a waitress for many months to earn enough money, and then I got out there and I met Lewis Leakey, and because I had read so many books, that was the work part. I read so many books on Africa, I spent hours in the Natural Museum, so I could answer all his questions, even though I wasn’t applying for a job he gave me one. So you don’t have to go straight there, it’s not necessarily school, college, job. It could be school, college, messing about while you discover what it is that you want to do.

Alastair Fothergill: The key thing is to discover what your passion is. A lot of people go all through their lives and never discover their passion. And I think the three of us have been very lucky that we discovered a passion for nature and that’s what’s given us lives and careers that every day, I wake up and I can’t believe people are paying me for doing what I’m doing, and it all has to do with having a passion.

What were some challenges filming in a remote location, and what were some of your favorite scenes to shoot?

Alastair Fothergill: I think the main challenge in making a movie rather than a TV documentary is that you can’t just film any behavior. It has to happen to Sky. We discovered very early on in our DisneyNature movies, that whenever we moved away from the star, and put other animals that we thought are fun, it just didn’t work. Everyone says “What’s happening to Sky? What’s happening to Amber? That’s all I really want to know.” If the film works. We’re lucky with Disney that they give us time to spend a very very long time in the field, we shot over of 400 hours of material for a 75 minute movie, hundreds of days in the field. Actually, Alaska’s not a difficult place to work, where we filmed the chimpanzee film was much more challenging, and we were very lucky to working with a fantastic team of people. We had a … small tourist cam, and they were perfect, because they got the logistics for us but also they had guides that for years, that had been out with the bears. So we were able to use their guides to help us. Alaskan weather can be challenging, but it’s a beautiful place to work. Favorite moments in the movie … I think the Golden Pond at the end of the movie and I absolutely loved the sequence when they’re in the woods, when just before the Golden Pond, when there’s that little mountain watching, I loved the beauty of that sequence after the big scene at the great falls, I love that moment, and I also love the moment when the cubs emerge from the den and they’re running through the mountains. That was unbelievably difficult to film. The joy that Sky has when she gets into the open air, you don’t have to say it, you can see, “I’ve been in a smelly den for 6 months, Hurrah, I’m out.” I love that.

Keith Scholey: For me it’s the moment when the wolf, Tikaani, comes up to Sky and the cubs and why that was so special is that these are grey wolves, so they are southern wolves, people have habituated arctic wolves, there are very few places where a grey wolf will tolerate a person. They’re basically been so persecuted. I think it’s only this one bay where this happens, so you’ve suddenly got a wolf that will accept you and run around you as close as you are to me. But we can then watch what wolves and bears do, and very few people have been able to watch what wolves and bears do and we didn’t know what happens when a wolf meets bear with cubs, we know that wolves take bear cubs. We watched this whole thing play out one evening and it was just extraordinary, we got two sequences for our film, but we were probably some of the first people to witness that encounter, it was really really special.

Can you speak about the outtakes and being so close to the bears?

Alastair Fothergill: It’s really funny with the outtakes, cause we do it after the TV shows as well, and people are always saying “I loved your movie, but the outtakes were the best bit,” We put them there because people are genuinely amazed by the situation and very surprised by how close you can get to bears, we just really wanted to help share the experience for people. It’s a way to keep people in the cinema a bit longer.

Keith Scholey: I think that as soon as you show the proximity of the camera with the bear you get it straight away, you think “okay that’s how they did this film” and I think that’s an important part of it as well, we want to say “Look this is how you can film bears in the wild,” We also wanted to overcome I think some of these things, and the bears are often portrayed as being really dangerous or really bad… In the right circumstances you can be with bears very safely.

How do you know those circumstances?

Keith Scholey: The first and foremost, if you go to a wilderness such as Katmai National Park, those bears have never had bad experiences with people. It is a huge open wilderness and the only people who go there are either people who are trained to look after the park or they’re guests who are brought into the park with trained people. So those bears have never been hunted and those bears have carefully have had no association with people or food or anything like that, so they just view people as part of the landscape. If you have those circumstances, I always liken it to “what’s the most dangerous animal on the planet?” It’s a person. It’s people. I’m sitting here with a whole bunch of people, I’m not afraid because I assume you’re not going all attack because the environment we are in right now is secure I understand the place, it’s been well managed and what have you. We can read that. You go into bear land and if it’s been well managed, you understand the people, you understand the relationship with bears, they are not dangerous. If you go to places where bears have had bad experiences with humans, they can a very dangerous animal … Bears don’t want trouble with people, they really don’t, but often they’ve been brought up or live through circumstances where they come into conflict and that’s not their fault. It’s nearly always the circumstances that they’ve been in.

The movie hits select theaters on April 18 and a portion of the proceeds from the opening weekend will be donated to the National Parks Foundation to help maintain the beautiful habitats of all animals.